Recently, we reported on plans by Australian entrepreneurs and their government to use ammonia (NH3) to store excess wind energy. We proposed converting ammonia and CO2 from wastewater into methane gas (CH4), because it is more stable and easier to transport. The procedure follows the chemical equation:

8 NH3 + 3 CO2 → 4 N2 + 3 CH4 + 6 H2O

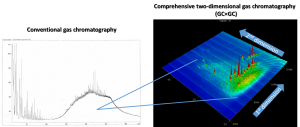

Now we have published a scientific article in the online magazine Frontiers in Energy Research where we show that the process is thermodynamically possible and does indeed occur. Methanogenic microbes in anaerobic digester sludge remove the hydrogen (H2) formed by electrolysis from the reaction equilibrium. As a result, the redox potentials of the oxidative (N2/NH3) and the reductive (CO2/CH4) half-reactions come so close that the process becomes spontaneous. It requires a catalyst in the form of wastewater microbes.

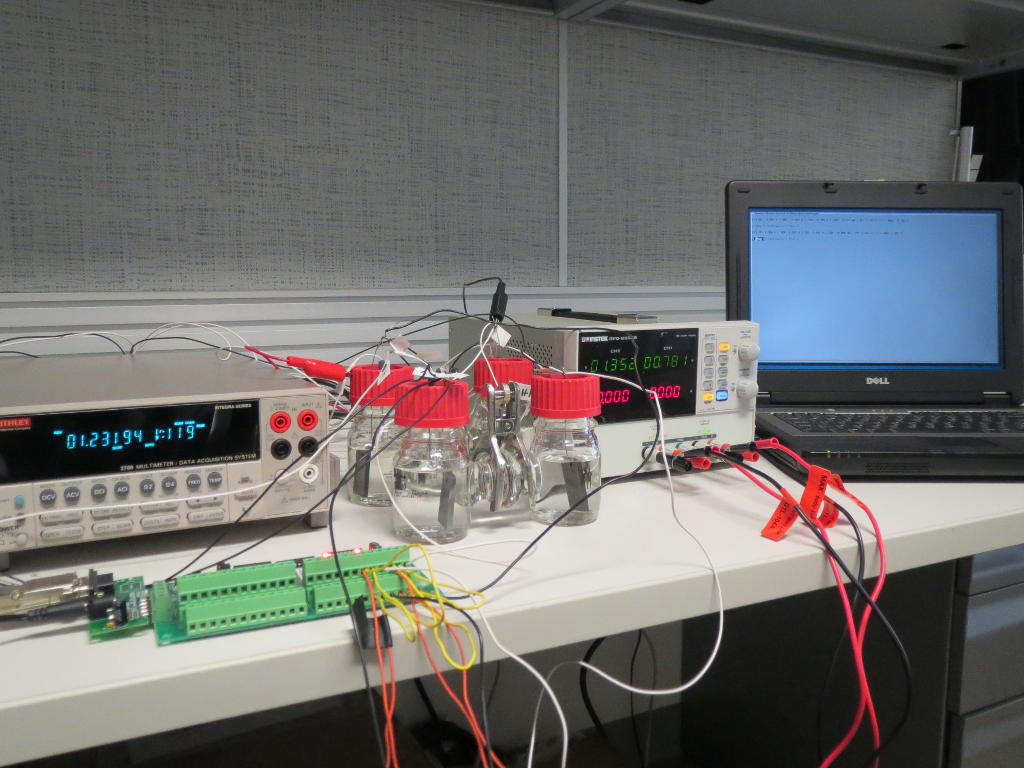

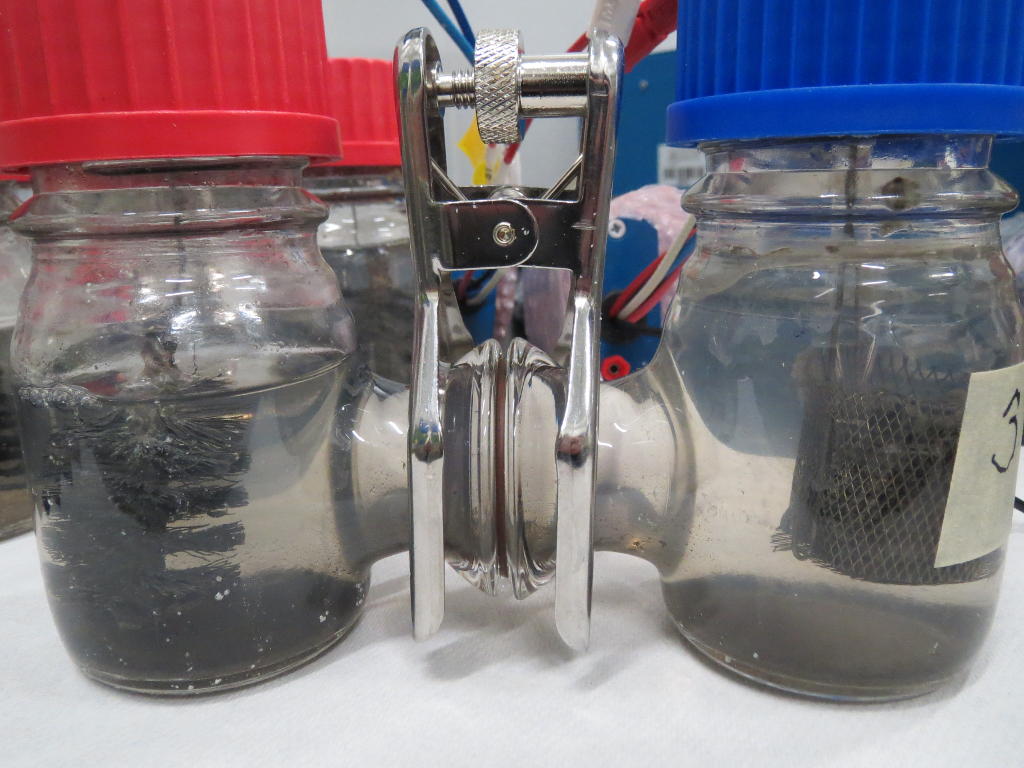

To prove our idea, we first searched for the right microbes that could carry out ammonia oxidation. For our experiments in microbial electrolysis cells we used microorganisms from sediments of the Atlantic Ocean off Namibia as starter cultures. Marine sediments are particularly suitable because they are relatively rich in ammonia, free from oxygen (O2) and contain less organic carbon than other ammonia-rich environments. Excluding oxygen is important because it used by ammonia-oxidizing microbes in a process called nitrification:

2 NH3+ + 3 O2 → 2 NO2− + 2 H+ + 2 H2O

Nitrification would have caused an electrochemical short circuit, as the electrons are transferred from the ammonia directly to the oxygen. This would have bypassed the anode (the positive electron accepting electrode) and stored the energy of the ammonia in the water − where it is useless. This is because, anodic water oxidation consumes much more energy than the oxidation of ammonia. In addition, precious metals are often necessary for water oxidation. Without producing oxygen at the anode, we were able to show that the oxidation of ammonium (the dissolved form of ammonia) is coupled to the production of hydrogen.

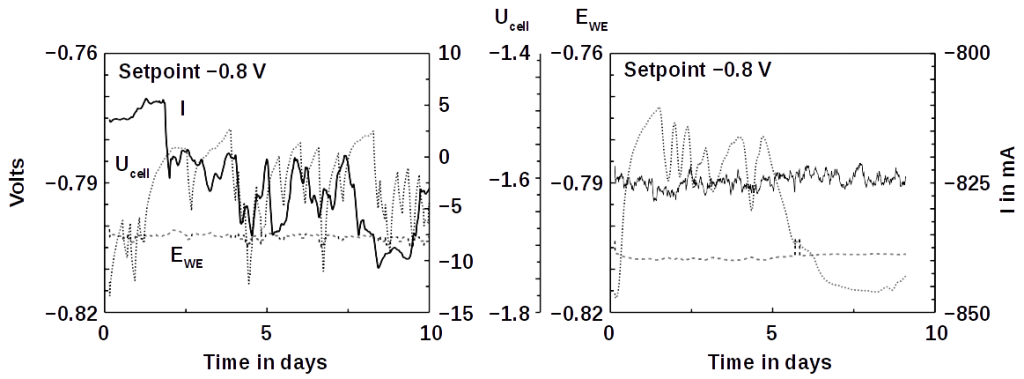

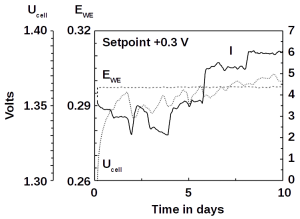

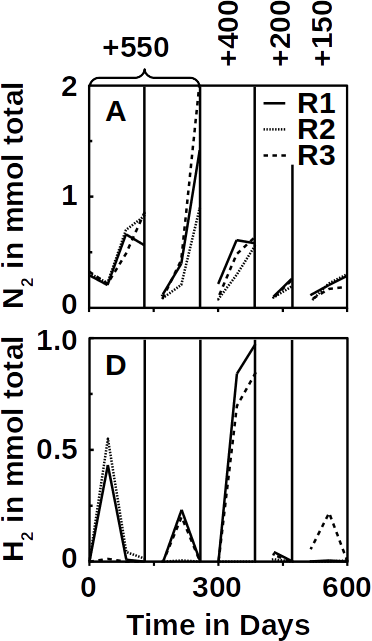

It was important that the electrochemical potential at the anode was more negative than the +820 mV required for water oxidation. For this purpose, we used a potentiostat that kept the electrochemical potential constant between +550 mV and +150 mV. At all these potentials, N2 was produced at the anode and H2 at the cathode. Since the only source of electrons in the anode compartment was ammonium, the electrons for hydrogen production could come only from the ammonium oxidation. In addition, ammonium was also the only nitrogen source for the production of N2. As a result, the processes would be coupled.

In the next step, we wanted to show that this process also has a useful application. Nitrogen compounds are often found in wastewater. These compounds consist predominantly of ammonium. Among them are also drugs and their degradation products. At the same time, 1-2% of the energy produced worldwide is consumed in the Haber-Bosch process. In the Haber-Bosch process N2 is extracted from the air to produce nitrogen fertilizer. Another 3% of our energy is then used to remove the same nitrogen from our wastewater. This senseless waste of energy emits 5% of our greenhouse gases. In contrast, wastewater treatment plants could be net energy generators. In fact, a small part of the energy of wastewater has been recovered as biogas for more than a century. During biogas production, organic material from anaerobic digester sludge is decomposed by microbial communities and converted into methane:

H3C−COO− + H+ + H2O → CH4 + HCO3− + H+; ∆G°’ = −31 kJ/mol (CH4)

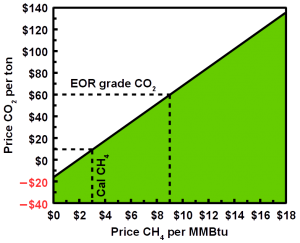

The reaction produces CO2 and methane at a ratio of 1:1. Unfortunately, the CO2 in the biogas makes it almost worthless. As a result, biogas is often flared off, especially in places where natural gas is cheap. The removal of CO2 would greatly enhance the product and can be achieved using CO2 scrubbers. Even more reduced carbon sources can shift the ratio of CO2 to CH4. Nevertheless, CO2 would remain in biogas. Adding hydrogen to anaerobic digesters solves this problem technically. The process is called biogas upgrading. Hydrogen could be produced by electrolysis:

2 H2O → 2 H2 + O2; ∆G°’ = +237 kJ/mol (H2)

Electrolysis of water, however, is expensive and requires higher energy input. The reason is that the electrolysis of water takes place at a relatively high voltage of 1.23 V. One way to get around this is to replace the water by ammonium:

2 NH4+ → N2 + 2 H+ + 3 H2; ∆G°’ = +40 kJ/mol (H2)

With ammonium, the reaction takes place at only 136 mV, which saves the respective amount of energy. Thus, and with suitable catalysts, ammonium could serve as a reducing agent for hydrogen production. Microorganisms in the wastewater could be such catalysts. Moreover, without oxygen, methanogens become active in the wastewater and consume the produced hydrogen:

4 H2 + HCO3– + H+ → CH4 + 3 H2O; ∆G°’ = –34 kJ/mol (H2)

The methanogenic reaction keeps the hydrogen concentration so low (usually below 10 Pa) that the ammonium oxidation proceeds spontaneously, i.e. with energy gain:

8 NH4+ + 3 HCO3– → 4 N2 + 3 CH4 + 5 H+ + 9 H2O; ∆G°’ = −30 kJ/mol (CH4)

This is exactly the reaction described above. Bioelectrical methanogens grow at cathodes and belong to the genus Methanobacterium. Members of this genus thrive at low H2 concentrations.

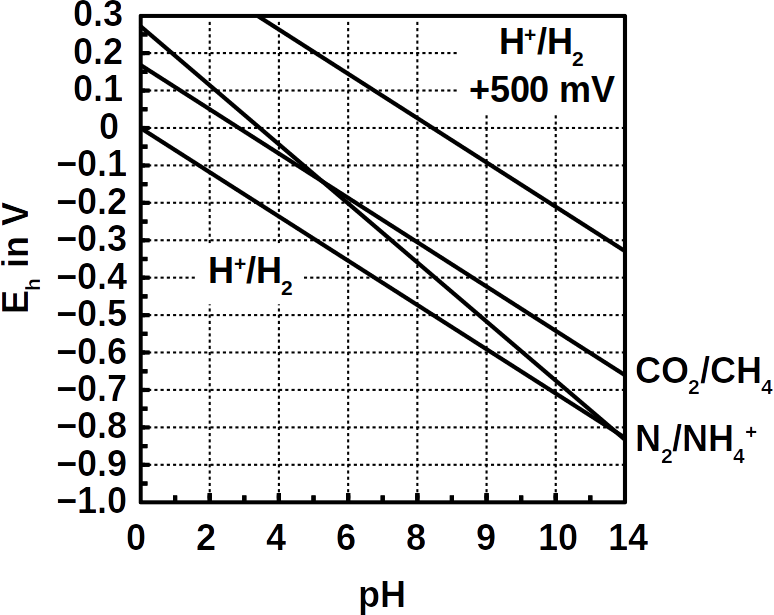

The low energy gain is due to the small potential difference of ΔEh = +33 mV of CO2 reduction compared to the ammonium oxidation (see Pourbaix diagram above). The energy captured is barely sufficient for ADP phosphorylation (ΔG°’ = +31 kJ/mol). In addition, the nitrogen bond energy is innately high, which requires strong oxidants such as O2 (nitrification) or nitrite (anammox) to break them.

Instead of strong oxidizing agents, an anode may provide the activation energy for the ammonium oxidation, for example when poised at +500 mV. However, such positive redox potentials do not occur naturally in anaerobic environments. Therefore, we tested whether the ammonium oxidation can be coupled to the hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis by offering a positive electrode potential without O2. Indeed, we demonstrated this in our article and have filed a patent application. With our method one could, for example, profitably remove ammonia from industrial wastewater. It is also suitable for energy storage when e.g. Ammonia synthesized using excess wind energy.