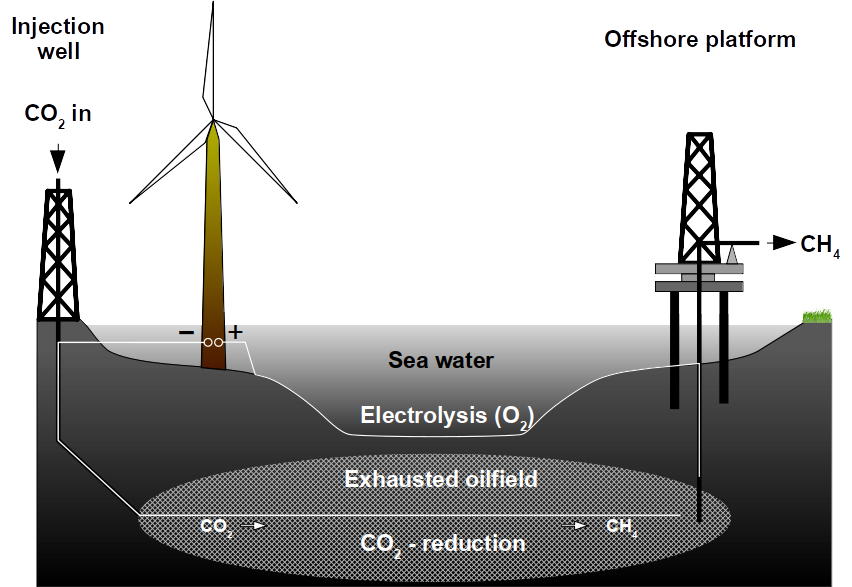

An abandoned or unproductive oilfield can be reused for methane production from CO2 using renewable electrical power. Exhausted oilfields can be reactors for the conversion of renewable energy to natural gas using microbes. To achieve this, an oilfield can be made electrically conductive and catalytically active to produce natural gas from renewable power sources. The use of natural gas is superior to any battery because of the existing infrastructure, the use in combustion engines, the high energy density and because it can be recycled from CO2. Oilfields are superior to any on-ground production because of the enormous storage capacities. They are already well explored and these geological formations underwent environmental risk assessments. Lastly, the microbial power-to-gas technology is already available.

Process summary

|

Whole process (end-to-end via methane) |

50% electrical efficiency |

|

Energy density of methane |

180 kWh kg−1 |

|

Storage capacity per oilfield |

3 GWh day−1 |

|

Charge/Discharge cycles |

Unlimited |

|

Investment (electrodes, for high densities) |

$51,000 MW−1 |

|

Cost per kWh (>5,000 hours anode lifetime) |

<$0.01 kWh−1 |

|

Electrolyte |

Seawater |

The Problem

To address the problem of storing renewable energy, batteries have been proposed as a possible solution. Lithium ion batteries have a maximum energy storage capacity of 0.3 kWh kg−1. To date, this is considered the best trade-off between cost and efficiency but these batteries are still too inefficient to replace gasoline, which has a capacity of about 13 kWh kg−1. This makes battery driven cars heavier than conventional cars. Lithium air batteries are considered a possible alternative because they can reach theoretical capacities of 12 kWh kg−1 but technical difficulties have prevented them from being used for transportation.

In contrast, methane has an energy density of 52 MJ kg−1 corresponding to 180 kWh kg−1 which is second only to hydrogen with 500 kWh kg−1, not counting in nuclear energy. This high energy density of methane and other hydrocarbons along with their facile usage, is the reason why they are used in combustion and jet engines that drive nearly all transportation to date. While electrical cars seem to be a tempting green alternative, the fact that combustion engines and the fueling infrastructure are so wide-spread makes it difficult to switch.

In addition to the difficulty of changing habits, battery-driven electrical cars need other limited natural resources such as lithium. To equip all 94 million automobiles produced worldwide in 2017, 3 mega tons lithium carbonate would need to be mined annually. This is nearly 10% of the entire recoverable lithium resources of 35 mega tons worldwide. Although lithium and other metals can be recycled, it is clear that metal based batteries alone will not build the bridge between green energy and traditional ways of transportation due to the low energy densities of metals. And this does not even take into account other energy demands such as industrial nitrogen fixation, aviation or heating.

For Germany, with its high proportion of renewable energy, fuel for cars is not the only problem. As renewable energy is generated in the north, but many energy consumers are in the south, the grid capacity is frequently reached during peak production hours. A steadier energy output can only be accomplished by decentralizing the production or by energy storage. To decentralize production, homeowners were encouraged to equip their property with solar panels or windmills. As tax incentives phase out, homeowners face the problem of energy storage. The best product for this group of customers so far are again lithium ion batteries but investment costs of $0.10 kWh−1 are still unattractive especially because these products store the energy as electricity which can only be used for a short time and is less efficient than natural gas when used for heating.

Natural gas is widely used as energy source today and the global energy infrastructure is designed for natural gas and other fossil fuels. Increasing demand and limited resources for these fossil fuels were the main drivers of oil and gas prices during the last years, slowed by the recent economic crises and hydraulic fracturing (fracking). The high oil price attracted investors to recover oil using techniques that become increasingly expensive and are environmental risks such as deep-sea drilling or tar sand extraction. Ironically, the high oil price made costly renewable energies an economically feasible alternative and helped driving down their cost. Since habits are difficult to change and building an entirely new infrastructure only for renewable energies does not seem economically feasible today while CO2 drives global warming, a more realistic solution needs to be found.

Microbial Power-to-Gas could be a bridging technology that integrates renewable energy into the existing fossil fuel infrastructure. It reaches break even in less than 2 years if certain preconditions are met. This is accomplished by integrating methane produced from renewable energy into the current oil and gas producing infrastructure. The principal idea is to use carbon instead of metals as energy carrier because of its high energy density when bound to hydrogen. The benefits are:

- High energy density of 180 kWh kg−1 methane

- Low investments due to existing infrastructure (natural gas, oilfield equipment)

- Carbon is not a limited resource

- Low CO2 footprint due to CO2 recycling

- Methane is a transportation fuel

- Methane is the energy carrier for the Haber-Bosch process

- Inexpensive catalysts further reduce initial investments

- Low temperatures due to bio-catalysis

- No toxic compounds used

- No additional environmental burden because existing oilfields are reused

The solution

Methane can be synthesized by microbes or chemically. Naturally, methane is produced by anaerobic (oxygen-free) microbial biomass decomposition. The energy for biomass synthesis is provided by sunlight or chemical energy like hydrogen. In the case of methanogens (methane producing microbes), energy is harvested after CO2 and hydrogen were released from biomass decomposition following a 1-to-4 stoichiometry:

CO2 + 4 H2 → CH4 + 2 H2O

Without microbes, methane is produced by the Nobel-prize winning Sabatier reaction and several attempts are currently underway to use it on industrial scale. It is necessary to split water into hydrogen and use this to reduce CO2 in the gas phase. A major drawback of the Sabatier reaction is the need for high temperatures around 385ºC, and a nickel catalyst that becomes quickly spent. Methanogens use iron-nickel enzymes called hydrogenases to harvest energy from hydrogen, but do so at ambient temperatures.

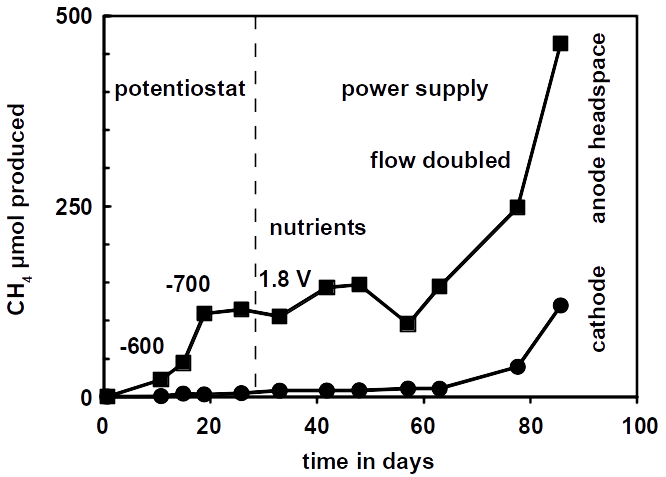

To produce abiotic hydrogen, water is split using precious metal catalysts. Microbes split water using hydrogenases in reverse direction and the produced hydrogen is oxidized by methanogens that grow in the electrolyte or on electrodes to produce methane. This reaction occurs at the correct 1-to-4 stoichiometry at potentials that are near to the theoretical hydrogen production potential of −410 mV obtained from the Nernst equation in neutral aqueous solutions. Methanogenic microorganisms are able to reduce the overpotential.

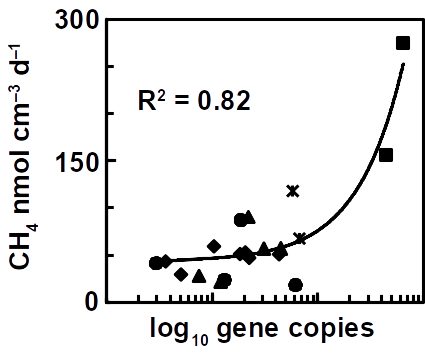

The future challenge will be to accelerate methane production rates as has been reported for a high temperature oilfield cultures. Besides increasing the temperature, the most obvious solution is to use a higher reactive surface and bringing both electrodes closer together. Using carbon brushes that are poor hydrogen catalysts but provide a higher surface for microbial attachment is one possibility. Methane production correlates with microbial cell numbers in the reactors.

To overcome the problem of expensive carbon (and also steel) brushes for large scale applications,exhausted gas and oilfields could be used. They provide a high surface area and are usually economic liabilities and not assets. Methanogens inhabit oilfields where they carry out the final step in anaerobic petroleum degradation. Hence, oilfields can be seen as bioreactors at geological scale. Geological formations provide ideal conditions for producing, storing and extracting methane.

Open questions and potential solutions

Oilfield porespace volume

The Californian Summerland oilfield, for instance, has been abandoned and extensively studied in the past. It produced 27 billion barrels of oil and 2.8 billion m3 methane during its lifetime of 90 years. This maximum load of 3.5 billion m3 left the same volume of porespace filled with seawater behind. Only 2% of these pores are larger than 50 µm, which is necessary for microbial growth assuming dimensions of 1 x 2 µm of a methanogen cell. Experiments showed that the resulting 70 million m3 accessible porespace have a storage capacity of 35,000 TW. That is a lot of methane assuming a solubility of 0.74 kg methane m−3 seawater at 500 m water depth. All German off-shore windfarms together have a capacity of 7,000 MW. Obviously, the limiting factor is not the volumetric storage capacity of an oilfield.

Microbial methane production rates

But how fast can microbes produce methane in an hypothetical oilfield? Under optimal conditions, methanogens that grow on electrodes (typically the genus Methanobacterium or Methanobrevibacter) can produce methane at a rate of 100-200 nmol ml−1 day−1 (equals 2.24-4.48 ml l−1 day−1) depending on catalyst and potential. Using a production rate of 15 J ml−1 day−1 of methane (190 nmol ml−1 day−1), the entire microbially accessible oilfield (2%) has a capacity of 3.6 million MBtu per year. Microbes would theoretically consume 1 TWh per year for 3.6 million MBtu methane production if there were no losses and electrical power is translated into methane 1-to-1. A power generator of 121 MW would be sufficient to supply the entire oilfield at these rates. However, all German off-shore windfarms produce 7,000 MW meaning that only 3% off-peak power can be captured by our example oilfield. Therefore, the catalytic surface and activity must be increased to accelerate methane conversion rates.

Since methanogens produce methane from hydrogen, not only the 2% porespace big enough for cells can be used resulting in an increased catalytic surface to nearly 60%. A hydrogen catalyst needs to be found that does not out-pace methanogen growth to keep the reservoir pH within the limits of 6-8 required for methanogen growth. This hydrogen catalyst must be cheap and render an oilfield electrically conductive. A chemical formulation that mimics microbial hydrogen catalysis could be used. It has the potential to turn a non-conductive and non-catalytic oilfield into a conductive hydrogen catalyst sufficient to sustain methane production needed to store all of Germany’s electricity produced by off-shore windfarms. This catalyst is soluble in water when inactive. To become active, it coats mineral surfaces by precipitation that can be triggered by indigenous microbes or by electrical polarization. The investment would be $2.3 million per MW storage capacity ($16 billion for the entire 7,000 MW). Due to microbial growth, the catalytic activity of the system improves during operation and there is no need for the second component if an immediate production is not crucial. The investments made on the cathode side would then be as low as $600 per MW ($4.2 million for 7,000 MW).

Anodes

As the cathodic side of the reaction can be excluded as limiting factor, the anode needs to be designed. Several commercially available anodes such as mixed metal oxides (up to 750 A m−2) with platinum on carbon black or niobium anodes (Pt/C, 5-10 kA m−2) could be used. Anodes based on platinum are the most cost-efficient material available on the market. Investments made for Pt/C (10%, 6 mg cm−2) anodes will amount to $50,000 per MW ($350 million for 7,000 MW). However, the exact amount of Pt needed for the reaction still needs to be evaluated in an experiment because the corrosion rate at 2 V cell voltage is unknown. An often cited value for the lifetime of fuel cells is 5,000 hours and is used here to determine the costs per kWh. For 5,000 hours lifetime, the costs per kWh will be at the targeted limit of $0.01 but may be well below that because Pt/C anodes can be recycled and the Pt load may be reduced to 3 mg cm−2 (5%). Alternatively, steel anodes (SS316, 2.5 kA m−2, $54,000 per MW) can be used but it is unclear when steel anodes fail to electrolyze. In conclusion, the anodic side is the cost-driving factor. Hopefully, better water splitting anodes will lower these costs in future.

Cost estimation summary

|

Windfarms |

Already in place |

|

CO2 injection |

Already occurred |

|

Natural gas capturing equipment |

Already in place |

|

Microbial seed |

Wastewater from oil rig |

|

Cathode costs |

$600 MW−1 |

|

Anode costs |

$50,000 MW−1 |

|

Electrolyte (seawater) |

Free |

|

Total (>5,000 hours anode lifespan) |

<$0.01 kWh−1 |

Energy and conversion efficiencies

The whole cell voltage for microbial power-to-gas reactions varies from 0.6 to 2.0 V, depending on cathodic rates, anodic corrosion and the presence of a membrane. Higher voltages will accelerate anode corrosion, again, making anodes the limiting factor. As the voltage decreases, methane production rates become slower but also more efficient. The voltage also depends on the pH of the oilfield. An oilfield that underwent CO2 injection as enhanced recovery method will have a low pH, providing better conditions for hydrogen production but not for microbial growth and must be neutralized using seawater. As stated above, the oilfield, being the cathode, is not limiting the the system. The use of Pt/C anodes eliminates the overpotential problem on the anode side. Hence, we can assume an ideal system that splits water at 1.23 V. However, the voltage is often 2 V due to anode and cathode overpotentials. Optimized cultures and cathodes produce about 190 nmol ml−1 day−1 methane which equals 0.15 J ml−1 day−1 using the energy of combustion of 0.8 MJ mol−1. The same electrolysis cell consumes 0.2 mW at a cell voltage of 2 V which equals 0.17 J ml−1 day−1 and the resulting energy efficiency is 91%. The anodes can be simple carbon brushes and the two chambers of the cell are separated by a Nafion™ membrane. The system can still be optimized by using Pt/C anodes and by avoiding membranes.

The overall electricity-methane-electricity efficiency also depends on the consumption side efficiency where methane is used in combustion engines and gas fired power plants. Such power plants frequently operate at efficiencies of 40- 60%. Assuming a reasonable power efficiency of 80% (see above), the overall electrical power recovery using gas fired power plants will be up to 50%. Besides the high efficiency of gas fired power plants, they are also easy to build and therefore contribute the a better power grid efficiency. Coal fired power plants can be upgraded to gas fired power plants.

Experimental approach

The conversion efficiencies of charge (Coulombs) transported across the circuit are usually between 70-100% in these systems depending on the electrode material. Another efficiency limitation could arise from mass transport inhibition. Mass transport can be improved by pumping electrolyte adding more costs for pumping which still have to be determined. However, since most oilfields undergo seawater injection for enhanced oil recovery the additional cost may be negligible. The total efficiency has yet to be determined in scale-up experiments and will depend on the factors mentioned above.

Controlling the pH is crucial. Alkaline pHs significantly impede hydrogen production and therefore methanogenesis. This can be addressed by a software that monitors the pH and adjusts the potential accordingly. Addition of acids is not desired as this drives the costs. The software can also act as potentiostat that then fully controls the methane production process. To test the process under more realistic conditions, a drill core from an oilfield must be obtained.

Return of investment of the microbial power-to-gas process

The the microbial power-to-gas process in unproductive oilfields is economically superior to all other storage strategies because of the low start-up and operating costs. This is achieved because the major investments are the installation of oil- and gas production equipment and renewable power plants which are already in place as a precondition. These investments break even in a short amount of time.

But how can the microbial Power-to-Gas process accelerate the return of investment in renewable energy? Only 8 out of 28 active off-shore windfarms reported their investment costs. These 8 produce roughly half the overall power of 1,600 MW corresponding to $7 billion. While the maximum production of an oilfield with unlimited supply of electricity would yield hypothetical 3.6 million MBtu natural gas per year resulting a return of $13 million per year the real production is limited by off-peak power generated by renewable energy production. Assuming that the maximum annual methane production corresponds to 10% excess electrical power, $15 million per year can by generated by selling 4.3 million MBtu methane per year on the market. These are $15 million that are not lost during off-peak shutdowns. Clearly, this conservative estimate can help to compensate the investment in renewable energy earlier. It also decreases the investment risk because the investment calculations for new wind farms can be made on a more reliable basis.

In the example using all German windfarms (7,000 MW) this compensation roughly doubles. Using the $60 million generated by methane sales per year, the investment of $4 million for the cathodic catalyst and the $36 million for the Pt/C anodes are compensated for within less than a year. No other investments are required because the target oilfield already produced oil and gas and all necessary installation are in working condition. The target oilfield is swept using seawater as secondary extraction method. Electrical installations are in place for cathodic protection of production equipment in order to prevent microbial corrosion, which, however, may need to be upgraded to pass the now higher power densities. Moreover, CO2 is used from CO2 injection as tertiary enhanced oil recovery method. Only the pH may then need to be adjusted to sustain life by sweeping with seawater.

And this is not the end of oilfield storage capacity. In theory, an oilfield can store the entire amount of renewable energy produced in one year globally, allowing more than enough head room for future development and CO2 sequestration.