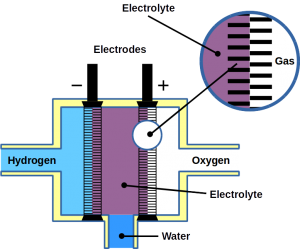

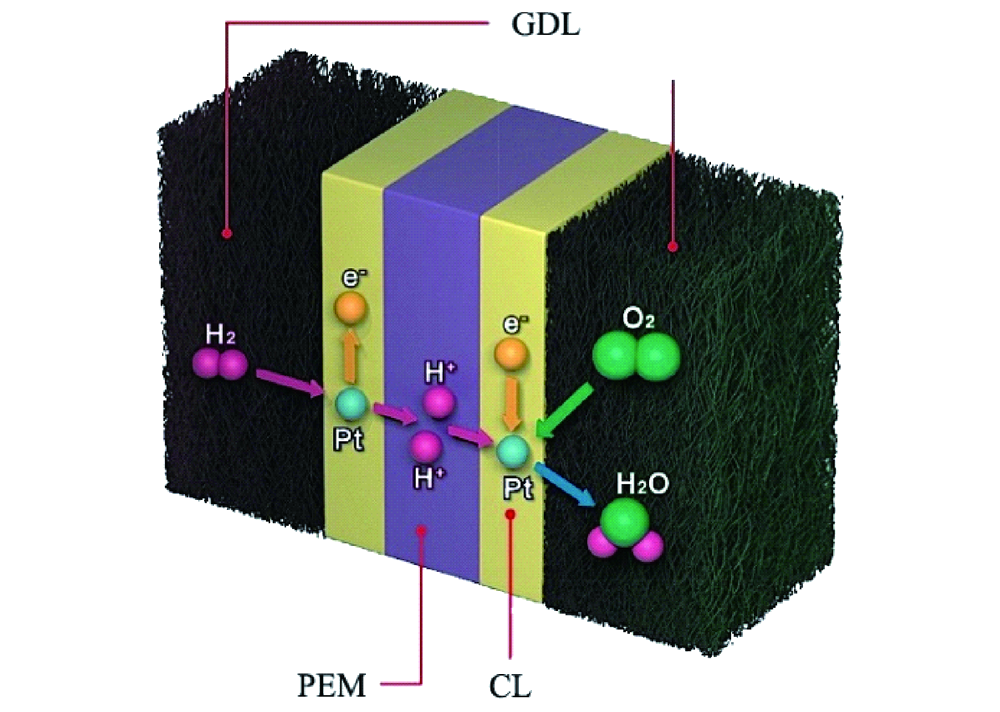

In electrochemical cells, such as fuel cells or electrolyzers, electric double-layer (EDL) formation occurs on their electrode surfaces. These EDL act as both, capacitors and resistors and impact therefore the performance of electrochemical cells. Understanding the structure and dynamics of EDL formation could significantly improve the performance of, electrochemical systems, for example in energy storage and conversion, including supercapacitors, water desalination, sensors and so forth.

On a planar electrode, electrolyte ions and the solvent are adsorbed at the electrode surface. The resulting capacitance depends on charge, solvation state and concentration. Traditionally, the capacitance of electrochemical interfaces can be divided into two types:

- Double-layer capacitance: ions are adsorbed based on their charge. Ion adsorption is non-specific.

- Faradaic pseudocapacitance: specific ions are adsorbed, for example through chemical interactions the electrode surface. This may involve charge transfer.

The electrode interface in the most energy application-based technology is, however, not planar but porous. Layer materials in such situations have various degrees of electrolyte confinement and thus different capacitive adsorption mechanisms. Understanding electrosorption in such materials requires a refined view of electrochemical capacitance and charge storage.

A team of researchers from the North Carolina State University, the Paul Sabatier University in Toulouse and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology reported new insights in electrolyte confinement at the non-planar interfaces in the journal Nature Energy.

Electric double-layer at planar electrodes

The degree of ion solvation (the process of reorganizing solvent and solute molecules) at ideal (planar) electrochemical interfaces determines the ions interaction with the electrodes. There are two distinct cases:

- Ions are non-specifically adsorbed: this is the case with strong ion solvation. The electrode’s interactions are primarily electrostatic. This type of interactions can be considered as the induction – charge is induced but not transferred.

- Ions are specifically adsorbed: in this case, ions are not solvated and can undergo specific adsorption and chemical bonding to the electrode. This process can be described as charge transfer reaction between the electrode and the adsorbed ion. However, the charge transfer reaction depends on the bonding between the ion and the electrode. This correlates with the state of ion solvation. Thus, it can be expected that the ion solvation is crucial for understanding the ion-electrode interactions in a nano-confined environment such as porous materials.

Carbon based EDL capacitor – the confinement effect

There is a great interest for understanding the relationship between the porosity of carbon nano-materials and their specific capacitance.

When electric double-layer formation occurs in a nano-confined micro-environment, the EDL capacitor in porous carbon materials deviates from the classic EDL model on flat interfaces. The degree of the ion solvation under confinement is determined by the pore size in nano-porous materials and by the inter-layer distance in layered materials that is, 2D-layer materials.

Confinement of ions in sub-nanometer pores results in their desolvation, leading to the capacitance increase and deviation from the typical linear behavior on the surface area. During negative polarization of porous carbon materials with the pore sizes <1 nm, a decrease of capacitance is observed. This is due to the ion selection limiting ion transport.

These insights are important for effectively tailoring carbon pore structures and for increasing their specific capacitance. Since carbon material is not an ideal conductor, it is important to consider its specific electric structure. For graphite materials, the availability of the charge carriers increases during the polarization which leads to increased conductivity.

Unified model of electrochemical charge storage under confinement

Since the electrochemical interface in the most technological application is non-planar, the researchers proposed a detailed evaluation and different concept of electrochemical capacitance on such non-ideal interfaces. The team evaluated electrosorption on 2D surfaces and 3D porous carbon surfaces with a continuous reduction in pore size in a step-by-step approach of increasing complexity.

The example provided relates to the charge storage characteristics of lithium ions (Li+) in the graphene sheets of organic lithium-containing electrolytes depending on the number of graphene layers. In a single graphene layer, the capacitive response is potential independent due to the absence of specific adsorption. However, with an increase of graphene sheets, redox peaks emerged that are associated with the intercalation of desolvated lithium ions. Lithium intercalation is responsible for battery wear. The team’s hypothesis was that the transition of solvated lithium ion adsorption on a single graphene sheet into subsequent intercalation of desolvated lithium ions occurs with a continuous charge storage behavior. There can be a seamless transition based on the increased charge transfer between an electrolyte ion and host associated with the extent of desolvation and confinement.

In the presented research, a unified approach was proposed that involves the continuous transition between double-layer capacitance and Faradaic intercalation under confinement. This approach excludes the traditional “single” view of electrochemical charge storage in nano-materials regarded as purely electrostatic or purely Faradaic phenomenon.

The increasing degree of ion confinement is followed by decreasing degree of ion solvation thus the increase ion-host intercalation. This results in a continuum from EDL formation through transitioning state to Faradaic intercalation, typical for EDLC nanomaterial.

Image: Pixabay