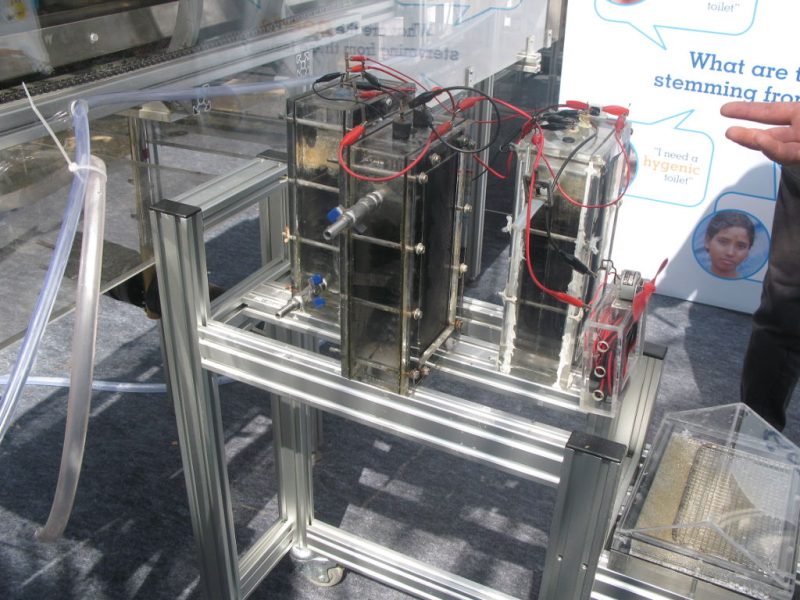

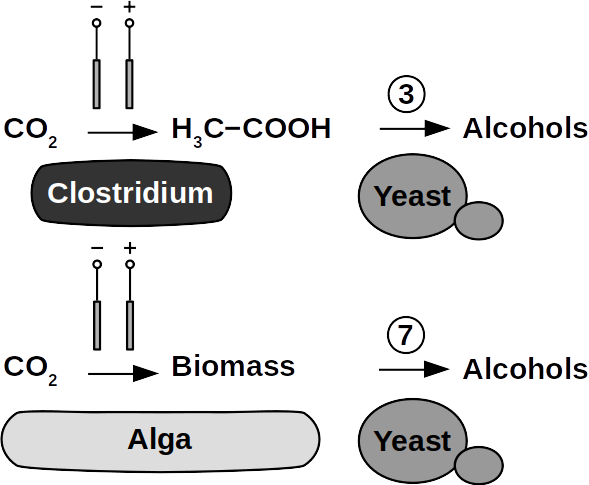

At Frontis Energy we have spent much thought on how to recycle CO2. While high value products such as polymers for medical applications are more profitable, customer demand for such products is too low to recycle CO2 in volumes required to decarbonize our atmosphere to pre-industrial levels. Biofuel, for example from field crops or algae has long been thought to be the solution. Unfortunately, they require too much arable land. On top of their land use, biochemical pathways are too complex to understand by the human brain. Therefore, we propose a different way to quickly reach the target of decarbonizing our planet. The procedure begins with a desired target fuel and suggests a microbial consortium to produce this fuel. In a second step, the consortium will be examined in a bio-electrical system (BES).

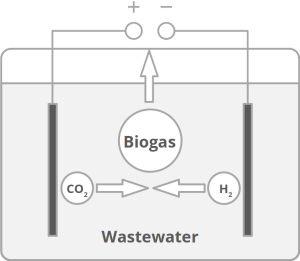

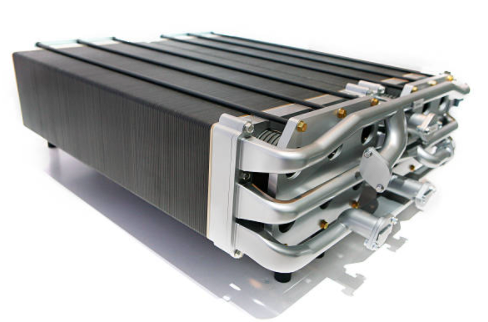

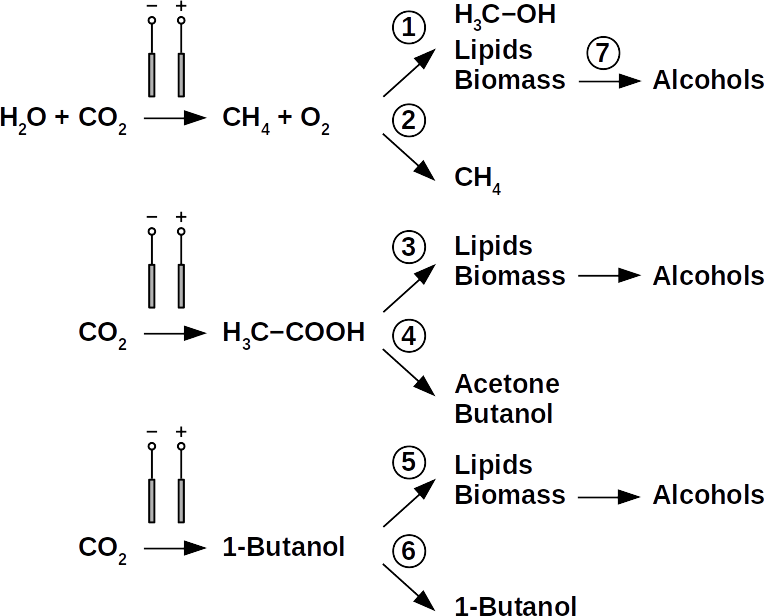

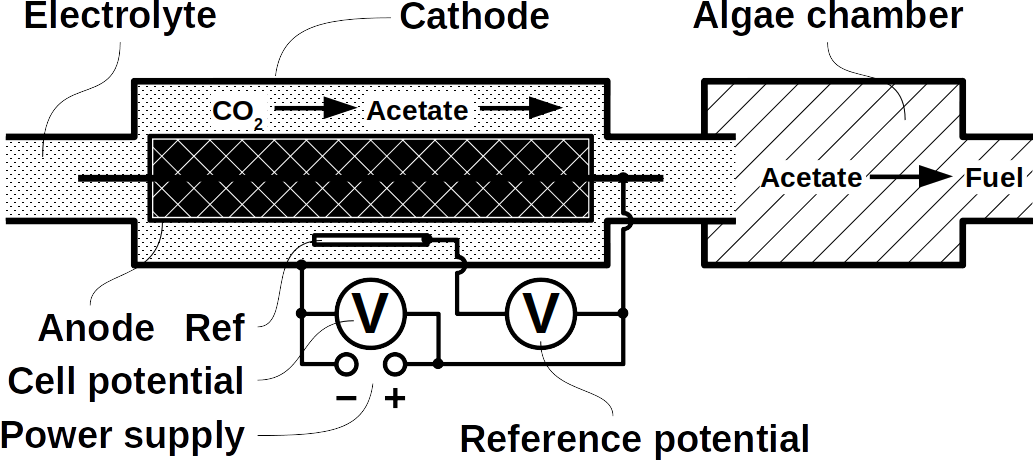

Today’s atmospheric CO2 imbalance is a consequence of fossil carbon combustion. This reality requires quick and pragmatic solutions if further CO2 accumulation is to be prevented. Direct air capture of CO2 is moving closer to economic feasibility, avoiding the use of arable land to grow fuel crops. Producing combustible fuel from CO2 is the most promising intermediate solution because such fuel integrates seamlessly into existing urban infrastructure. Biofuels have been explored intensively in recent years, in particular within the emerging field of synthetic biology. However tempting the application of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) appears, non-GMO technology is easier and faster to implement as the required microbial strains already exist. Avoiding GMOs, CO2 can be used in BES to produce C1 fuels like methane and precursors like formic acid or syngas, as well as C1+ compounds like acetate, 2-oxybutyrate, butyrate, ethanol, and butanol. At the same time, BES integrate well into urban infrastructure without the need for arable land. However, except for methane, none of these fuels are readily combustible in their pure form. While electromethane is a commercially available alternative to fossil natural gas, its volumetric energy density of 40-80 MJ/m3 is lower than that of gasoline with 35-45 GJ/m3. This, the necessary technical modifications, and the psychological barrier of tanking a gaseous fuel make methane hard to sell to automobilists. To produce liquid fuel, carbon chains need to be elongated with alcohols or better, hydrocarbons as final products. To this end, syngas (CO + H2) is theoretically a viable option in the Fischer-Tropsch process. In reality, syngas precursors are either fossil fuels (e.g. coal, natural gas, methanol) or biomass. While the former is obviously not CO2-neutral, the latter competes for arable land. The direct conversion of CO2 and electrolytic H2 to C1+ fuels, in turn, is catalyzed out by electroactive microbes in the dark (see title figure), avoiding food crop competition for sun-lit land. Unfortunately, little research has been undertaken beyond proof of concept of few electroactive strains. In stark contrast, a plethora of metabolic studies in non-BES is available. These studies often propose the use of GMOs or complex organic substrates as precursors. We propose to systematically identify metabolic strategies for liquid bio-electrically engineered fuel (BEEF) production. The fastest approach should start by screening metabolic databases using established methods of metabolic modeling, followed by high throughput hypothesis testing in BES. Since H2 is the intermediate in bio-electrosynthesis, the most efficient strategy is to focus on CO2 and H2 as direct precursors with as few intermediate steps as possible. Scalability and energy efficiency, economic feasibility that is, are pivotal elements.

The biggest obstacle for BEEF production is lacking knowledge about pathways that use CO2 and electrolytic H2. This gap exists despite metabolic databases like KEGG and more recently KBase, making metabolic design and adequate BEEF strain selection a guessing game rather than an educated approach. Nonetheless, metabolic tools were used to model fuel production in single cell yeasts and various prokaryotes. In spite of their shortcomings, metabolic databases were also employed to model species interactions, for example in a photo-heterotroph consortium using software like ModelSEED / KBase (http://modelseed.org/), RAVEN / KEGG and COBRA. A first systematic attempt for BEEF cultures producing acetate demonstrated the usability of KBase for BES. This research was a bottom-up study which mapped existing genomes onto existing BEEF consortia. The same tool can also be employed in a top-down approach, starting with the desired fuel to find the required organisms. Some possible BEEF organisms are the following.

Yeasts are among the microorganisms with the greatest potential for liquid biofuel production. Baker’s yeast, (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is the most prominent example. While known for ethanol fermentation, yeasts also produce fusel oils such as butane, phenyl, and amyl derivate aldehydes and alcohols. Unlike ethanol, which is formed via sugar fermentation, fusel oil is synthesized in branched-off amino acid pathways followed by aldehyde reduction. Many enzymes involved in the reduction of aldehydes have been identified, with alcohol dehydrogenases being the most commonly observed. The corresponding reduction reactions require reduced NADH but it is not known whether H2 produced on cathodes of BES can be involved.

Clostridia, for example Clostridium acetobutylicum and C. carboxidivorans, can produce alcohols like butanol, isopropanol, hexanol, and ketones like acetone from complex substrates (starch, whey, cellulose, etc. ) or from syngas. Clostridial metabolism has been clarified some time ago and is different from yeast. It does not necessarily require complex precursors for NAD+ reduction and it was shown that H2, CO, and cathodes can donate electrons for alcohol production. CO2 and H2 were used in a GMO clostridium to produce high titers of isobutanol. Typical representatives for acetate production from CO2 and H2 are C. ljungdahlii, C. aceticum, and Butyribacterium methylotrophicum. Sporomusa sphaeroides produces acetate in BES. Clostridia also dominated mixed culture BESs converting CO2 to butyrate. They are therefore prime targets for low cost biofuel production. Alcohols in clostridia are produced from acetyl-CoA. This reaction is reversible, allowing acetate to serve as substrate for biofuel production with extracellular energy supply. Then, energy conservation, ATP synthesis that is, can be achieved from ethanol electron bifurcation or H2 oxidation via respiration. While possible in anaerobic clostridia, it is hitherto unknown whether electron bifurcation or respiration are linked to alcohols or ketone synthesis.

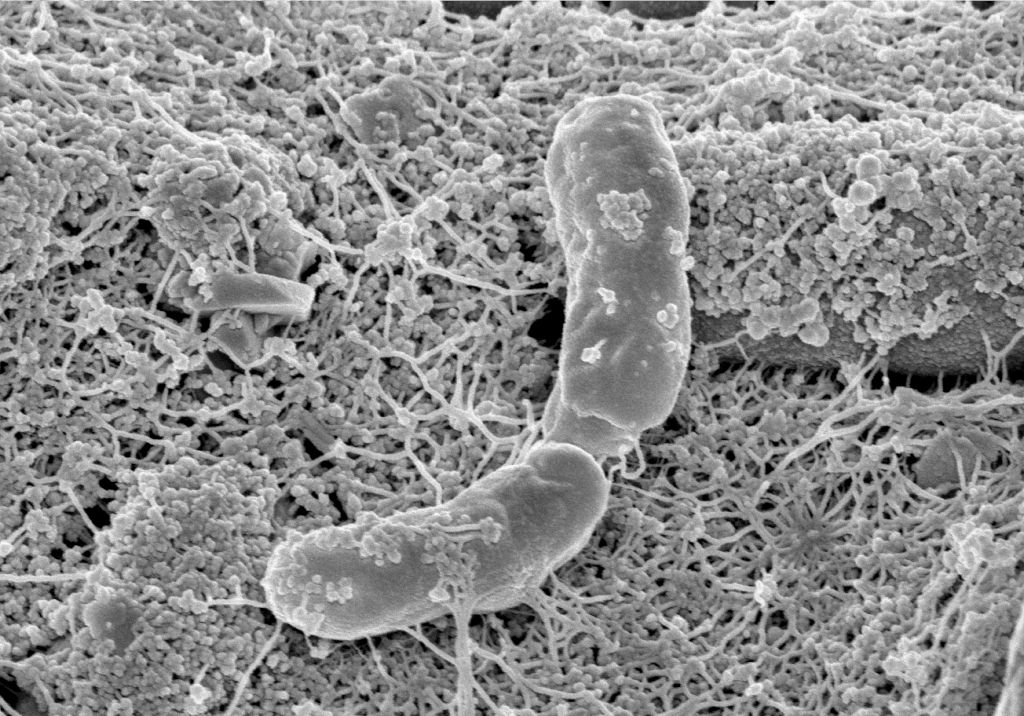

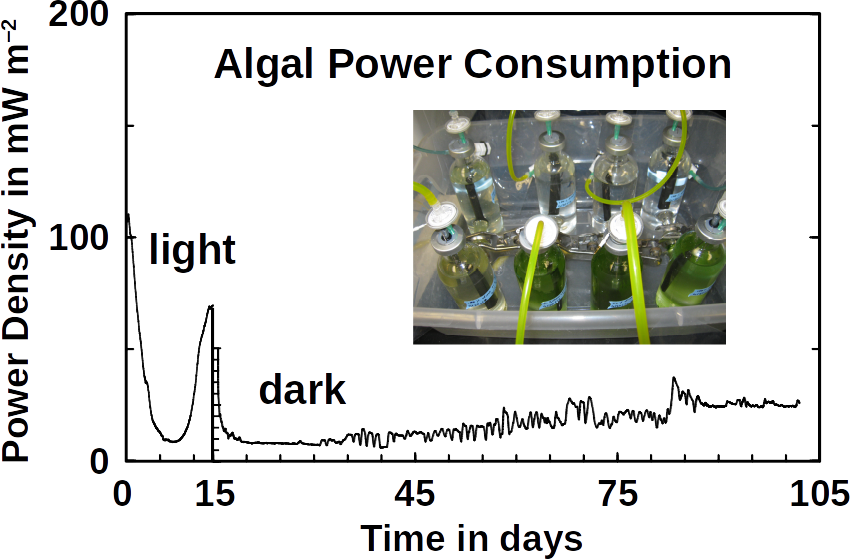

Phototrophs like Botryococcus produce C1+ biofuels as well. They synthesize a number of different hydrocarbons including high value alkanes and alkenes as well as terpenes. However, high titers were achieved by only means of genetic engineering, which is economically not feasible in many countries due to regulatory constrains. Moreover, aldehyde dehydration/deformylation to alkanes or alkenes requires molecular oxygen to be present. Also the olefin pathway of Synechococcus depends on molecular oxygen with the cytochrome P450 involved in fatty acid decarboxylation. The presence of molecular oxygen affects BES performance due to immediate product degradation and unwanted cathodic oxygen reduction. In contrast, our own preliminary experiments (see title photo) and a corrosion experiment show that algae can live in the dark using electrons from a cathode. While the enzymes involved in the production of some algal biofuels are known (such as olefin and aldehyde deformylation), it is not known whether these pathways are connected to H2 utilization (perhaps via ferredoxins). Such a connection would be a promising indicator for the possibility of growing hydrocarbon producing cyanobacteria on cathodes of BES and should be examined in future research.

At Frontis Energy we believe that a number of other microorganisms show potential for BEEF production and these deserve further investigation. To avoid GMOs, BES compatible co-cultures must be identified via in silico metabolic reconstruction from existing databases. Possible inter-species intermediates are unknown but are prerequisite for successful BES operation. Finally, a techno-economical assessment of BEEF production, with and without carbon taxes, and compared with chemical methods, will direct future research.