In wastewater treatment, aeration is an energy-intensive but necessary process to remove contaminants. Pumps blow air into the wastewater to supply the microbes in the treatment tank with oxygen. In return, these bacteria oxidize organic substances to CO2 and hence remove them from the wastewater. This process is the industrial standard and has proven itself for over a century. If the researchers at Washington State University and the University of Idaho have their way, that is changing now.

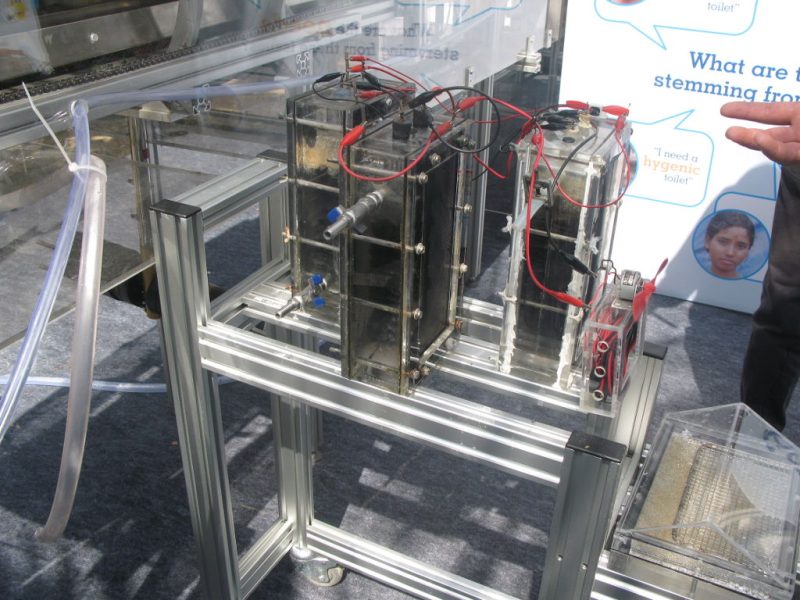

In their project, the researchers used a unique microbial fuel cell system they developed to replace aeration. Their novel wastewater treatment system cleans wastewater with the help of microorganisms that produce electricity. These microbes are called electrophiles.

The work should one day lead to less dependence on the energy-intensive treatment processes. Most of the energy in such processes is consumed in the activated sludge and its disposal. The energy consumption in water treatment produces around 4-5% of anthropogenic CO2 worldwide. to put that in perspective, according to the Air Transport Action Group in Geneva, international air transport produced 2.1% CO2 in 2019. The researchers published their work in the journal Bioelectrochemistry. In addition to cutting green house gas emissions, lowering the energy consumption of wastewater treatment would save billions in annual operation and maintenance costs.

Microbial fuel cells allow microbes to convert chemical energy into electricity, much like in a battery. In wastewater treatment, a microbial fuel cell can replace aeration while capturing electrons from wastewater organics. These electrons themselves are in turn a waste product of the microbial metabolism. All living organisms strive to discharge their excess electrons. This process is known as respiration or fermentation. The electricity generated the microbes can be used for useful applications in the wastewater treatment plant itself. The technology kills two birds with one stone. On the one hand, the treatment of the wastewater saves energy. On the other hand, it also generates electricity.

Up until now, microbial fuel cells have been used experimentally in wastewater treatment systems under ideal conditions, but under real and changing conditions they often fail. Microbial fuel cells lack regulation that controls the potential of anodes and cathodes and thus the cell potential. This can easily lead lead to a system failure. The entire cell must then be replaced.

To tackle this problem, the researchers added an additional reference electrode to the system that enables them to control their fuel cell. The system becomes more flexible. It can either work as a microbial fuel cell on its own and consume no energy, or it can be converted so that less energy is used for aeration while it purifies the wastewater more intensively. Frontis Energy uses a similar control system for its electrolysis reactors.

The system was operated for one year without major issues in the laboratory as well as a pilot in a wastewater treatment plant in Idaho. It removed contaminants at rates comparable to those in a classic aeration tanks. In addition, the microbial fuel cell could possibly be used completely independent of grid power. The researchers hope that one day it could be used in small wastewater treatment plants, such as cleaning livestock farms or in remote areas.

Despite the progress, there are still challenges to be overcome. They are complex systems that are difficult to build. At Frontis Energy we specialize in such systems and can help with piloting and commercialization.