In our last post on water quality in China, we pointed out a study that shows how improved wastewater treatment has a positive effect on the environment and ultimately on public health. However, wastewater treatment requires sophisticated and costly infrastructure. This is not available everywhere. However, extracting resources from wastewater can offset some of the costs incurred by plant construction and operation. The question is how much of a resource is wastewater.

A recent study published in the journal Natural Resources Forum tries to answer that question. It is the first to estimate how much wastewater all cities on Earth produce each year. The amount is enormous, as the authors say. There are currently 380 billion cubic meters of wastewater per year worldwide. The authors omitted only 5% of urban areas by population.

The most important resources in wastewater are energy, nutrients like nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus, and the water itself. In municipal wastewater treatment plants they come from human excretions. In industry and agriculture they are remnants of the production process. The team calculated how much of the nutrient resources in the municipal wastewater is likely to end up in the global wastewater stream. The researchers come to a total number of 26 million tons per year. That is almost eighty times the weight of the Empire State Building in New York.

If one would recover the entire nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium load, one could theoretically cover 13% of the global fertilizer requirement. The team assumed that the wastewater volume will likely continue to increase, because the world’s population, urbanization and living standards are also increasing. They further estimate that in 2050 there will be almost 50% more wastewater than in 2015. It will be necessary to treat as much as possible and to make greater use of the nutrients in that wastewater! As we pointed out in our previous post, wastewater is more and more causing environmental and public health problems.

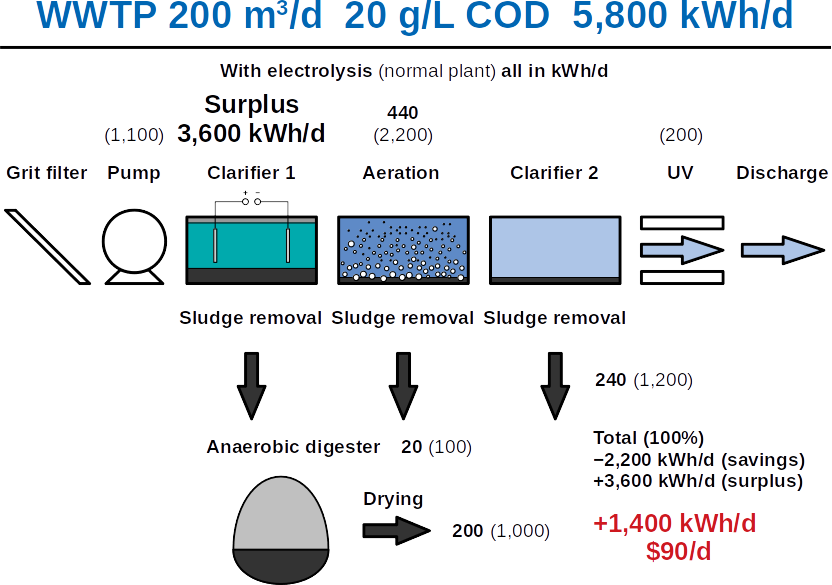

There is also energy in wastewater. Wastewater treatment plants industrialized countries have been using them in the form of biogas for a long time. Most wastewater treatment plants ferment sewage sludge in large anaerobic digesters and use them to produce methane. As a result, some plants are now energy self-sufficient.

The authors calculated the energy potential that lies hidden in the wastewater of all cities worldwide. In principle, the energy is sufficient to supply 500 to 600 million average consumers with electricity. The only problems are: wastewater treatment and energy technology are expensive, and therefore hardly used in non-industrialized countries. According to the scientists, this will change. Occasionally, this is already happening.

Singapore is a prominent example. Wastewater is treated there so intensively that it is fed back into the normal water network. In Jordan, the wastewater from the cities of Amman and Zerqa goes to the municipal wastewater treatment plant by gravitation. There, small turbines are installed in the canals, which have been supplying energy ever since their construction. Such projects send out a signals that resource recovery is possible and make wastewater treatment more efficient and less costly.

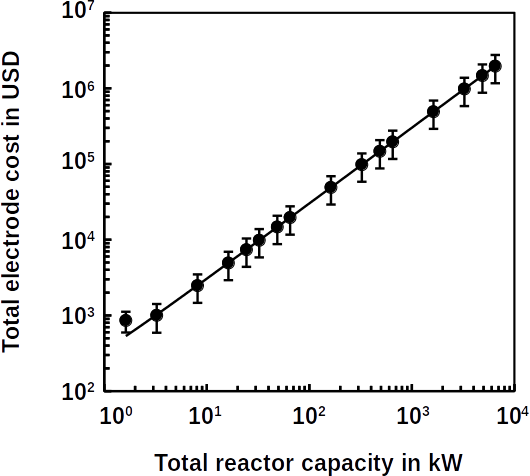

The Frontis technology is based on microbial electrolysis which combines many of the steps in wastewater treatment plants in one single reactor, recovering nutrients as well as energy.

(Photo: Wikipedia)