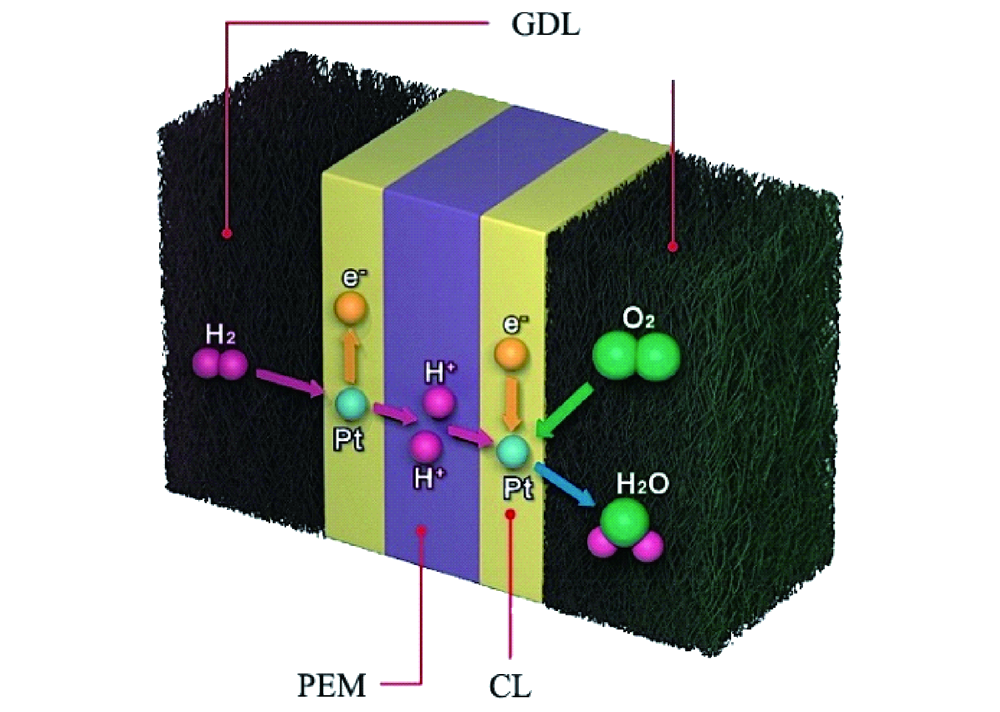

Hydrogen fuel cells are often regarded as a key element in the green energy transition. Their efficiency is double the thermochemical energy conversion of internal combustion engines. Hydrogen fuel cells convert the chemical energy of hydrogen and oxygen directly into electricity and water. Hence, water plays a central role in fuel cells. It supports ion transport and participates is product of the reaction itself. In an anion exchange membrane fuel cell (AEMFC), for the oxygen reduction reaction to take place, the water in the anode catalyst layer (ACL) must diffuse to the cathode catalyst layer (CCL). In summary, water management is required to remove water from the ACL for higher efficiency of hydrogen diffusion and to balance the water in the entire membrane electrode assembly (MEA).

Significant research efforts have been made to achieve conditions that is suitable for both the anode and cathode in AEMFC. Asymmetric humidification of reactant gases was proposed to be beneficial to achieve well equilibrated water balance between the two electrodes. At higher temperatures, excess anode water evaporates. It also causes deficiencies at the cathode which also requires water to function. To counteract this, a new system that controls the back pressure at the anode and cathode was introduced. However, external control mechanisms (active control) increase the complexity of the system control.

This is where a passive control system involving MEA modification comes into the picture. Moisture control in a fuel cells can be achieved by designing a suitable gas diffusion layer. Adopting different types of hydrophobic materials for the anode and hydrophilic for the cathode can improve overall fuel cell performance. Poly ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) copolymer ion exchange membranes, such as Nafion™ have high water mobility. This property can help water back diffusion to avoid anode flooding while preventing dehydration of the cathode. Designing a gradient microstructure or ionomer content within the CCL could also be useful to improve cell performance and durability.

Recent research published in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science addresses these questions. The presented study was carried out to assess a multi-layer CCL design with the gradient capillary force which has a driving effect on water to solve the water balance problem of anodes in AEMFC. For the purpose of the study, platinum on carbon and platinum-ruthenium on carbon were selected as anode catalysts. Ruthenium increases the hydrogen oxidation reaction activity and possesses beneficial structural properties. Water management and performance of AEMFC would be influenced by the structure of the ACL.

Microstructure analysis of ACLs

ACLs composed of different layers of Pt/C and PtRu/C and a mixed version with a similar thickness of around 9-10 µm were analyzed with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX).

Pt/C ACL had pores of less than 150 nm while PtRu/C catalysts pores ranged between 300-400 nm. The mixed ACL had a pore size <200 nm.

The researchers concluded that Pt/C and PtRu/C ACL had a stratified and gradient pore size distribution spanning across the anion exchange membrane and the gas diffusion layer. The mixed ACL, however, had a homogenous pore structure throughout the MEA.

Moisture adsorption and desorption behavior of ACLs

To investigate moisture adsorption and desorption, the change of the fuel cell’s moisture content was checked with regards to different levels of relative humidity.

It was observed that the moisture content level increased by up to 50% mass weight along with an increase in relative humidity from 20% to 80%.

With an extended equilibrium time for a relative humidity of 80%, the moisture content of Pt/PtRu and PtRu/Pt ACL began to decrease. This was evidence for the self-adjusting water management behavior.

Desorption at a relative humidity of 60% was done. The water content in ACL showed rapid adsorption and slow-release properties at each relative humidity setting.

Physical adjustment of water behavior was observed in PtRu/Pt ACLs. This was attributed to gradient nano-pores and promoted water transport when water was generated within the ACLs during the electrochemical reactions. It would facilitate fuel cells operation at high current density.

Fuel cell performance of ACLs

To assess the structural effect on water management during operation, fuel cell performance was investigated at different relative humidity and temperature levels.

With increasing relative humidity from 40% to 80%, an increase of the maximum power density was observed as well while the temperature remained constant at 50°C. This was due to higher ionic conductivity at high membrane hydration.

At relative humidity of 100%, a maximum power density of the Pt/PtRu MEA and the mixed MEA decreased, however. The inverted MEA version using PtRu/Pt an increase to 243 mW/cm2 was observed. This suggested that the moisture desorption ability of PtRu/Pt MEA promoted mass transfer during fuel cell operation.

At a temperature of 60°C and 100% relative humidity, the maximum power density of PtRu/Pt reached 252 mW/cm2.

A durability test was conducted for PtRu/Pt MEA. It showed that after continuous operation for more than 16 hours at 100 mA/cm2 the voltage drop was <4%.

Conclusion

It became clear from the tests that the PtRu/Pt anode catalyst layer with its homogenous layer had a better self-adjustment capability for fuel cell water management. The gradient nanopore structure of the catalyst layer made it possible to transport water through the capillary effect. Excess water at the anode could either be transported towards the cathode where it would be used for reaction or towards the gas diffusion layer for its removal prevented flooding. Moreover, this catalyst layer made from PtRu/Pt showed better performance abilities too.

At Frontis Energy we think that this could resolve the issues faced with water management in the fuel cells. Since it is a passive control system that involves modifying the design of the fuel cells internally, intricate external systems could be replaced or complemented. The study certainly helps future fuel cell automation as an interesting new aspect of fuel cell design was discovered that could make them smarter.