The demand for energy is increasing and raw material for the fossil fuel economy is diminishing. Moreover, the emission of gases from fossil fuel usage significantly degrades air quality. The carbon by-products produced from these fossil fuels severely affect the climate.

Hence, there is a need to find a renewable energy resource, that can be produced, stored, and used easily as per requirement. Hydrogen can be a promising energy resource as it is an abundantly available, non-toxic resource, and can be readily used to store excess electrical energy.

Hydrogen when combined with oxygen in a fuel cell produces electricity and the by-products obtained are water and heat. Based on the method of production of hydrogen it is categorized as blue hydrogen and green hydrogen. Blue hydrogen is produced from fossil fuels such as methane, gasoline, coal while green hydrogen is produced from non-fossil fuels / water. The cleanest way to produce eco-friendly hydrogen is via electrolysis of water where water is electrolyzed to separate hydrogen and oxygen. Renewable energy can be used as a power electrolyzer to produce hydrogen from water. Solar driven photo electrochemical (PEC) water splitting is one of the common method used these days. In photo electrochemical (PEC) water splitting, hydrogen is produced from water using sunlight.

PEC cells comprise of a working photoelectrode and a counter electrode. The photoelectrode consists of semiconductor material with a band gap to absorb solar light and generate an electron-hole pair. The photo-generated charges are responsible for the oxidation of water and its reduction into hydrogen. The PEC suffer devices from low stability and efficiency.

The research team from the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) along with researchers from the Institute of Chemistry and Processes for Energy, Environment and Health (ICPEES) , a CNRS-University of Strasbourg joint research lab published a way to significantly improve the efficiency of water dissociation to produce hydrogen by the development of sunlight photosensitive-nanostructured electrodes.

A comparative study between cobalt and nickel oxide nanoparticles deposited onto TiO 2 nanotubes prepared through anodization was carried out. The TiO 2 nanotubes were decorated with CoO (cobalt oxide) and NiO (nickel oxide) nanoparticles using the reactive pulsed laser deposition method. The surface loadings of CoO or NiO nanoparticles were controlled by the number of laser ablation pulses. The efficiency of CoO and NiO nanoparticles as co-catalysts for photo-electrochemical water splitting was studied by cyclic voltammetry, under both simulated sunlight and visible light illuminations and by external quantum efficiency measurements

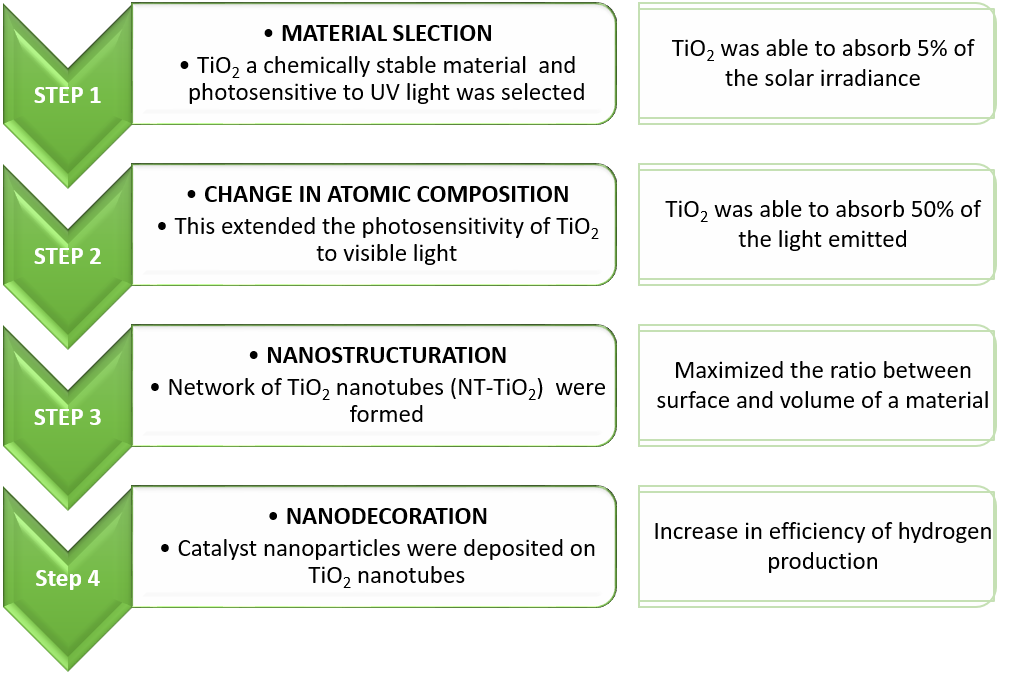

The entire research work was carried out in the following steps:

(Source: Favet et al ., Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells , 2020)

In this study Cobalt (CoO) and Nickel (NiO) oxides were considered as effective co-catalysts for splitting water molecules. Both co-catalysts improved photo-electrochemical conversion of ultra violet as well visible light photons.

However, CoO nanoparticles were found to be the best co-catalyst under visible light illumination, with a Photo Conversion Efficiency almost 10 times higher than for TiO 2 . The performance of CoO nanoparticles got enhanced in the visible spectral region (λ> 400 nm). The possible reason can be a consequence of their visible bandgap which enables them to harvest more photon in the 400-500 nm range and transferring effectively the photo-generated electrons to TiO 2 nanotubes.

At Frontis Energy we are exited about these new discovery to improve hydrogen production from sunlight and hope to see an industrial application soon.

(Image: Engineersforum)

Reference: Favet et al ., Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells , 2020