Recently we reported the loss of snow cover in Europe. The snow is not only gone in many parts of Europe, also Greenland’s ice cover is melting. The Greenland ice sheet contributes 25% to global sea-level rise. This makes it the largest contribution of the cryosphere. The increased mass loss of Greenland ice during the 21st century is mainly due to the increased surface water runoff, of which ~93% come directly from the small ablation zone of the ice sheet (~22% of the ice surface). As the snow melts in the summer, bare glacier ice is more exposed in this ablation zone. Naked ice is darker and less porous than snow. It absorbs more than twice the solar radiation while also holding back less meltwater. Smooth ice produces a large proportion (~78%) of the total outflow of Greenland into the sea, although in summer only a small area of the ice is exposed. Accurately capturing the reduced albedo and the full extent of bare ice in climate models is critical to determining Greenland’s present and future runoff contribution to sea-level rise.

The mass loss of the Greenland ice sheet has recently increased due to the accelerated melting of its surface. As this melting is critically affected by surface albedo, understanding the processes and potential feedbacks regardinng the albedo is required for accurately forecasting mass loss. The resulting radiation variability of the ablation zone caused the ice layer to melt five times faster compared with hydrological and biological processes, which also darken the ice sheet. Variations in the snow limits due to the shallower ice layer at higher altitudes have an even greater impact on melt when the climate is warmer. As a result of these fluctuations, the mapped ice surface during the summer of 2012, the record year of snowmelt, was the largest and had an area of 300,050 km2. That is, bare ice accounted for 16% of the ice surface. The smallest extent of bare ice was 184,660 km2 and was observed in 2006. This corresponded to 10% of the ice surface, i.e. almost 40% less area than in 2012. However, the observed snowpack variation was high and the observation period was too short for a solid trend assessment.

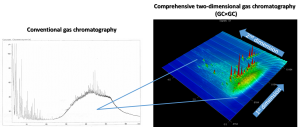

Current climate models are too inaccurate in predicting the sea level rise during flood years, leading to uncertainty in the estimation of Greenland’s contribution to global sea level rise. To understand the factors that influence melting, Jonathan Ryan of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, and his colleagues have investigated Greenland’s snow line. At altitudes below the snow line, the darker ice is not covered by snow. This snow line moves up or down during Greenland’s seasons. The researchers mapped these movements between 2001 and 2017 using satellite images. The average height of the snow line at the end of the summer in 2009 was between 1,330 m and then 1,650 m in 2012. The fluctuations in the snow line are the most important factor when it comes to how much solar energy the ice sheet absorbs. Modelers must consider this effect to improve their predictions. Knowing how much and how fast the Greenland ice melts will help us to take better protective measures. At Frontis Energy, we think that the best protection against sea-level rise is the prevention and recycling of CO2.

(Photo: Wikipedia)